Science fiction and fantasy may still be underappreciated by literary connoisseurs, whoever they are, although the iconic work that has made these ‘genres’ last often holds all of the qualities of literary fiction. It goes without saying that the production of soap-opera series with a ‘sci-fi aesthetic’ is a different matter.

In reality, though, there is no conspiracy against sci-fi. On the contrary, it is quite popular, as evidenced by the constant influx of new titles, yet, as with any other trend, perhaps the aesthetic is all there is to it.

On what science-fiction is not, let us listen to Philip K. Dick, if you’ll allow me to cite: ‘[Science fiction] cannot be defined as “a story (or novel or play) set in the future,” since there exists such a thing as space adventure, which is set in the future but is not sf: it is just that: adventures, fights and wars in the future in space involving super-advanced technology.’

Rehashing space opera, first contact or dystopian scenarios is not what I look for in science fiction. Sure, we all enjoy a good story, and the same old hero with a thousand faces may always provide what we look for in one, but it’s not as black and white as changing the setting and the protagonist’s looks and interests. (On a related note, I do not believe in writing to market, but I’ll leave that for another post.)

Why are the Hunger Games so popular? Hasn’t anyone read Battle Royale? Most probably haven’t, despite Stephen King’s recommendation, but it’s actually beyond the point whether something is a rip-off. What’s important is that there is something for everyone in both, and it pertains to our own society, despite the fact that it might be argued that only one of the books does justice to its grim premise, besides being the objectively better book. Science fiction may usually be set in the future, but it is always predicated on our own society and its history.

Perhaps the burden of ‘genre’ is why some major authors have distanced themselves from any attachment to science fiction, such as, for example, Kurt Vonnegut, whose work embodies all the specific qualities that have made science fiction what it is for many of us; namely, the uninhibited exploration of ideas and concepts. Generic pulp is certainly a thing with its own grateful audience, but why call it science fiction? It’s misleading, in the least. It might be why ‘speculative fiction’ has gotten a lot of use over the years. To conclude, I’d like to quote Dick again:

‘[Science fiction] is creative and it inspires creativity, which mainstream fiction by-and-large does not do. (…) the very best science fiction ultimately winds up being a collaboration between author and reader, in which both create—and enjoy doing it: joy is the essential and final ingredient of science fiction, the joy of discovery of newness.’

Such is the most beautiful definition of science fiction (and fiction in general) I’ve ever read. More importantly, it rings true. It’s the reason why I’m here, writing these words. Furthermore, it is applicable to other arts, such as music; especially jazz, which some may deem “music for musicians” (despite the extraordinary range of actual music under the moniker), and which, at its best, may most certainly be seen as Philip K. Dick’s “creativity-inspiring creativity. “

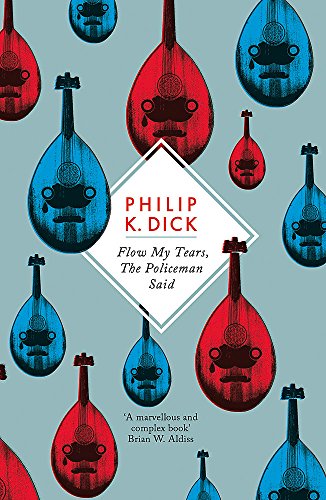

For proof or at least further insight, one may consider the amazing cover art featured at the top. It belongs to an edition of Dick’s Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said. Weird for a science fiction cover, right? Do I really think it’s good, you may ask? It may not tell you anything, yet it speaks of its own meaning. It’s subjective, even self-indulgent, though not as much as it seems. It depicts no policemen, cyborgs, spaceships or planets, basically nothing of the sort that we’re used to seeing in the genre. Yes, it may be abstract, but it is by no means unintelligible, and it ties into Dick’s original abstraction, i.e. the title of the novel, taken from the most famous air for lute by 16th century English (“or possibly Irish”) composer John Dowland, Flow my tears, fall from your springs.

That said, I have no idea who the artist behind it is (please let me know if you do), but I’m certain that he or she is a true Dickhead! The choice of an oud – an ancient fretless lute, predominantly a Middle-Eastern instrument, with its characteristic ‘sad face’ and the minimalist addition of a tear below one of its rosettas – works for what becomes the most important reason when judged it by Dick’s definition of science fiction. The cover art doesn’t attempt to paint a scene from within; it is not an image from the story. Instead, it is in itself an inspired work by the artist, a direct creative answer to Dick’s creative question; in turn, the cover art inspires a creative reaction in the willing observer, painting the very purpose of science fiction.